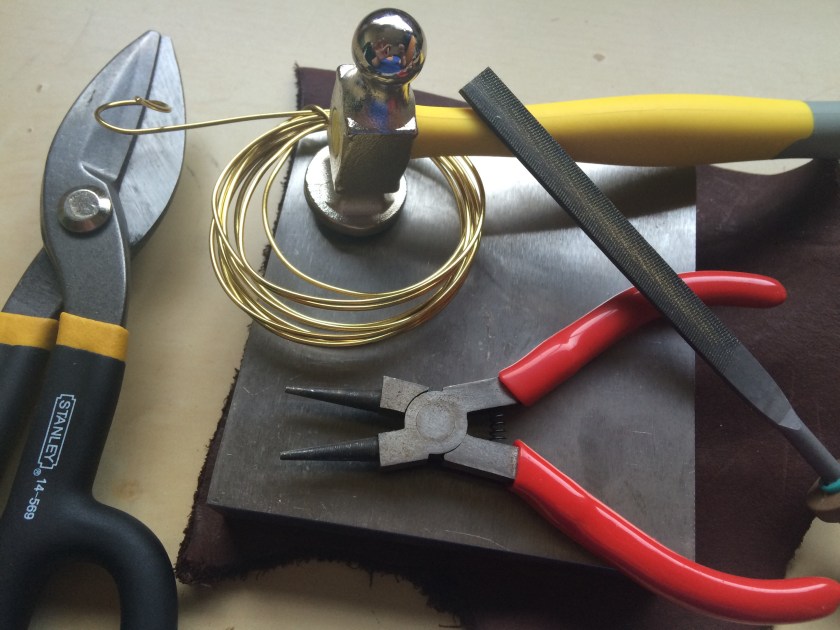

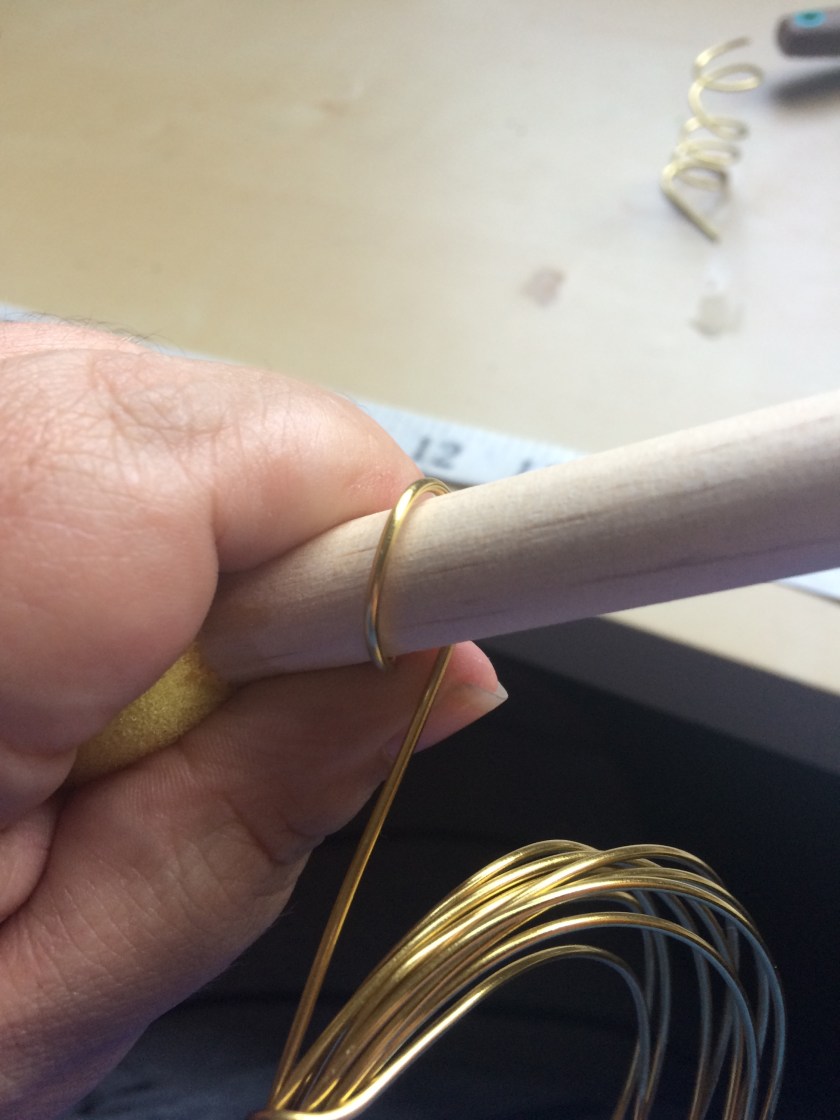

Confession: I like shiny things. I have a weak spot for jewelry. Now that I’m a wealthy guildwoman, I feel entitled to wear some baubles. While I can make my own simple things like beaded necklaces and wire pins, for anything nicer I go to the professionals. Here are some jewelers I’ve purchased from whom I recommend.

Laurel Cavanaugh, aka The Mad Jeweler, SKA Mistress Morgan(?) of the West Kingdom; Facebook, Etsy shop. Put simply, she does stunning work, from replica pieces of medieval and renaissance jewelry to modern interpretations to SCA-specific designs (like regalia). I have a laurel ring from her that was given to me at my elevation that is one of my most prized possessions on this earth, partly because of the love that came with it and partly because it’s just so beautiful. Highly recommended!

Izmir Jewelry, not a SCAdian. Etsy shop. I ran across this Etsy seller one day while browsing everything tagged “Roman jewelry.” Their work is inexpensive vermeil (gold-plated silver) and has a distinct and recognizable look (hammered, relatively rough stones, etc.) that I happen to really like. I bought a ring on a whim, and loved it so much that now pretty much every time I need a little retail therapy I get myself a ring or some earrings. (Don’t judge.) Shipping is surprisingly fast to the US. Because these are plated, they won’t last forever and they won’t stand up to much abuse. The gold is honestly already wearing off on my rings. But for something that I got to be costume pieces, they do what I want them to do, which is be big and shiny and look passably medieval (more passably Roman) while still being something I could take camping without fear.

Twilight Forge — Etsy Shop. Source for cast bronze / brass brooches and pins. I have a set of La Tene brooches to wear with my Iron Age Celtic clothing and I had a pair of beautiful quatrefoil brooches but I seem to have lost one of them last summer 😦 Edited to add: I found the missing brooch last weekend! Yay!!! This seller has great prices and fast shipping.